Go Set a Watchman is a novel by Harper Lee that was published in 2015 by HarperCollins (US) and Heinemann (UK). Written before her only other published novel, To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Go Set a Watchman was initially promoted as a sequel by its publishers. It is now accepted that it was a first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, with many passages in that book being used again.[2][3][4]

The title comes from the Book of Isaiah in the Hebrew Bible: "For thus hath the Lord said unto me, Go, set a watchman, let him declare what he seeth" (Chapter 21, Verse 6),[5] which is quoted in the book's seventh chapter by Mr. Stone, the minister character. It alludes to Jean Louise Finch's view of her father, Atticus Finch, as the moral compass ("watchman") of Maycomb, Alabama,[6] and has a theme of disillusionment, as she discovers the extent of the bigotry in her home community. Go Set a Watchman tackles the racial tensions brewing in the South in the 1950s and delves into the complex relationship between father and daughter. It includes treatments of many of the characters who appear in To Kill a Mockingbird.[7]

A significant controversy around the decision to publish Go Set a Watchman centered on the allegations that 89-year-old Lee was taken advantage of by her publishers and pressured into allowing publication against her previously stated intentions.[8] Later, when it was realized that the book was an early draft as opposed to a distinct sequel, it was questioned why the novel had been published without any context.[9]

HarperCollins, United States, and William Heinemann, United Kingdom, published Go Set a Watchman on July 14, 2015. The book's unexpected discovery, decades after it was written, and the status of the author's only other book as an American classic, caused its publication to be highly anticipated.[10][9][11] Amazon stated that it was their "most pre-ordered book" since the final novel in the Harry Potter series, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, in 2007,[12] and stores arranged all-night openings beginning at midnight to cope with expected demand.[13] Go Set a Watchman set a record for the highest adult novel one-day sales at Barnes & Noble, which included digital sales and pre-orders made before July 14. Barnes & Noble declined to release the exact number.[14]

Plot

Jean Louise "Scout" Finch, 26 and single, returns from New York to her hometown of Maycomb, Alabama, for her annual fortnight-long visit to her father Atticus, a lawyer and former state legislator. Jack, her uncle and a retired doctor, is Jean Louise's mentor. Atticus' sister (Jean Louise's aunt), Alexandra, has moved in with Atticus to help him around the house after his housekeeper, Calpurnia, retired. Jean Louise's brother, Jeremy "Jem" Finch, has died of the same heart condition which killed their mother. Upon her arrival in Maycomb, Jean Louise is met by her childhood sweetheart Henry "Hank" Clinton, who works for Atticus. When returning from Finch's Landing, Jean Louise and Henry are passed by a car full of black men travelling at a dangerously high speed; Henry mentions that the black people in the county have money for cars but are without licenses and insurance.

The Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) are introduced as sources of controversy in the community. Jean Louise finds a pamphlet titled "The Black Plague" among her father's papers. She follows him to a Citizens' Council meeting where Atticus introduces a man who delivers a racist speech. Jean Louise watches in secret from the balcony and is horrified. She is unable to forgive him for his behaviour and flees from the hall. After dreaming about Calpurnia, her family's black maid whom she sees as a mother figure, Jean Louise has breakfast with her father. They soon learn that Calpurnia's grandson killed a drunk pedestrian the previous night while speeding in his car. Atticus agrees to take the case in order to stop the NAACP from getting involved. Jean Louise visits Calpurnia and is treated politely but coldly, causing her to leave, devastated.

While at lunch, Jean Louise wants to know why Atticus was at the meeting. Uncle Jack tells her that Atticus has not suddenly become a racist but he is trying to slow down federal government intervention into state politics. Her uncle lectures her on the complexity of history, race, and politics in the South in an attempt to get Jean Louise to come to a conclusion, which she struggles to grasp. She then has a flashback to when she was a teenager and recalls an incident where Atticus planted the seed for an idea in Henry's brain, then let him come to the right conclusion on his own. Jean Louise tells Henry that she does not love him and will never marry him. She expresses her disgust at seeing him with her father at the council meeting. Henry explains that sometimes people have to do things they don't want to do. Henry then defends his own case by saying that the reason that he is still part of the Citizens' Council is because he wants to use his intelligence to make an impact on his hometown of Maycomb and to make money to raise a family. She screams that she could never live with a hypocrite, only to notice that Atticus is standing behind them, smiling.

During a discussion with his daughter, Atticus argues that the blacks of the South are not ready for full civil rights, and the Supreme Court's decision was unconstitutional and irresponsible. Although Jean Louise agrees that the South is not ready to be fully integrated, she says the court was pushed into a corner by the NAACP and had to act. She is confused and devastated by her father's positions as they are contrary to everything he has ever taught her. She returns to the family home furious and packs her things. As she is about to leave town, her uncle comes home. She angrily complains to him, and her uncle slaps her across the face. He tells her to think of all the things that have happened over the past two days and how she has processed them. When she says she can now stand them, he tells her it is bearable because she is her own person. He says that at one point she had fastened her conscience to her father's, assuming that her answers would always be his answers. Her uncle tells her that Atticus was letting her break her idols so that she could reduce him to the status of a human being.

Jean Louise returns to the office and makes a date with Henry for the evening. She reflects that Maycomb has taught him things she had never known and rendered her useless to him except as his oldest friend. She goes to apologize to Atticus, but he tells her how proud of her he is. He hoped that she would stand for what she thinks is right. She reflects that she did not want her world disturbed but that she tried to crush the man who is trying to preserve it for her. Telling him that she loves him very much as she follows him to the car, she silently welcomes him to the human race. For the first time, she sees him as just a man.

Development history

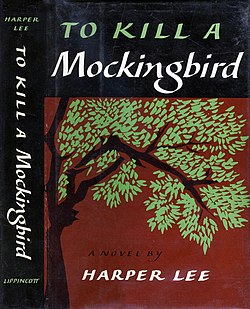

Initially, Go Set a Watchman was promoted by its publisher, and described in media reports, as a sequel to Lee's best-selling novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, which was published in 1960, but it is actually the first draft of that novel.[2][15] The novel was finished in 1957[15] and purchased by the J.B. Lippincott Company. Lee's editor, Tay Hohoff, was impressed by elements of the story, and stated that "the spark of the true writer flashed in every line",[15] but she thought that it was by no means ready for publication, being, as she described it, "more a series of anecdotes than a fully conceived novel". In his Times article on Hohoff, Jonathan Mahler states that Hohoff thought the strongest aspect of Lee's novel was the flashback sequences featuring a young Scout, which is why she asked Lee to use those flashbacks as a basis for a new novel. Lee agreed, and "during the next couple of years, Hohoff led Lee from one draft to the next until the book finally achieved its finished form and was retitled To Kill a Mockingbird."[15]

According to Mahler, "Ms. Hohoff also references a more detailed characterization of the development process, found in the Lippincott corporate history: 'After a couple of false starts, the story-line, interplay of characters, and fall of emphasis grew clearer, and with each revision—there were many minor changes as the story grew in strength and in her own vision of it—the true stature of the novel became evident.' (In 1978, Lippincott was acquired by Harper & Row, which became HarperCollins, publisher of Watchman.)"[15] Mahler remarks that "there appeared to be a natural give and take between author and editor. 'When she disagreed with a suggestion, we talked it out, sometimes for hours,' Ms. Hohoff wrote. 'And sometimes she came around to my way of thinking, sometimes I to hers, sometimes the discussion would open up an entirely new line of country.'"[15]

Various theories have been offered as to why the initial characterization of Atticus as a segregationist was dropped in the later novel. Mahler suggests that it could have been Hohoff who inspired the change.[15] Raised "in a multigenerational Quaker home near Prospect Park in Brooklyn, Hohoff attended a Quaker school, Brooklyn Friends. Such an upbringing suggests certain progressive values. But probably the clearest window into her state of mind when she was coaching Ms. Lee through the rewrite of Mockingbird is the book she was writing herself at the time: a biography of John Lovejoy Elliott, a social activist and humanist in early-20th-century New York who had committed his life to helping the city's underclass. The book, A Ministry to Man, was published in 1959, one year before Mockingbird."[15]

Michiko Kakutani noted the changes between the two versions: "Some plot points that have become touchstones in Mockingbird are evident in the earlier Watchman. Scout's older brother, Jem, vividly alive as a boy in Mockingbird, is dead in Watchman; the trial of a black man accused of raping a young white woman ... is only a passing aside in Watchman. (The trial results in a guilty verdict for the accused man, Tom Robinson, in Mockingbird but leads to an acquittal in Watchman.)" She continues, "Students of writing will find Watchman fascinating for these reasons: How did a lumpy tale about a young woman's grief over her discovery of her father's bigoted views evolve into a classic coming-of-age story about two children and their devoted widower father? How did a distressing narrative filled with characters spouting hate speech (from the casually patronizing to the disgustingly grotesque—and presumably meant to capture the extreme prejudice that could exist in small towns in the Deep South in the 1950s) mutate into a redemptive novel associated with the civil rights movement, hailed, in the words of the former civil rights activist and congressman Andrew Young, for giving us 'a sense of emerging humanism and decency?'"[16]

Kakutani also states that not only are characterizations and plot points different, the motivation behind the novel shifts as well: "Somewhere along the way, the overarching impulse behind the writing also seems to have changed. Watchman reads as if it were fueled by the alienation of a native daughter — who, like Lee, moved away from small-town Alabama to New York City — might feel upon returning home. It seems to want to document the worst in Maycomb in terms of racial and class prejudice, the people's enmity and hypocrisy and small-mindedness. At times, it also alarmingly suggests that the civil rights movement roiled things up, making people who "used to trust each other" now "watch each other like hawks".[16]

According to Kakutani, "Mockingbird, in contrast, represents a determined effort to see both the bad and the good in small-town life, the hatred and the humanity; it presents an idealized father-daughter relationship (which a relative in Watchman suggests has kept Jean Louise from fully becoming her own person) and views the past not as something lost but as a treasured memory. In a 1963 interview, Lee, whose own hometown is Monroeville, Ala., said of Mockingbird: 'The book is not an indictment so much as a plea for something, a reminder to people at home.'"[16]

The papers of Annie Laurie Williams and Maurice Crain, who were Harper Lee's literary agents in the 1950s, are held at Columbia University's Rare Book & Manuscript Library. They show that Go Set a Watchman was an early draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, and underwent significant changes in story and characters during the revision process. Harper Lee was writing Go Set a Watchman in January 1957, and sold the manuscript to the publisher J. B. Lippincott in October 1957. She then continued to work on the manuscript for the next two years, submitting revised manuscripts to her literary agents. At some point in that two-year period, Lee renamed her book To Kill a Mockingbird. Some of these records have been copied and posted online.[17]

Discovery

The manuscript was long thought to have been lost. According to The New York Times, the typed manuscript of Go Set a Watchman was first found, during an appraisal of Lee's assets in 2011, in a safe deposit box in Lee's hometown of Monroeville.[18][19] Lee's lawyer, Tonja Carter, later revealed that she had first assumed the manuscript to be an early draft of To Kill a Mockingbird. Later, upon learning in the middle of 2014 of the existence of a second novel at a family gathering, she then re-examined Lee's safe-deposit box and found the manuscript for Go Set a Watchman. After contacting Lee and reading the manuscript, she passed it on to Lee's agent, Andrew Nurnberg.

Lee released a statement through her attorney in regards to the discovery:

- "In the mid-1950s, I completed a novel called Go Set a Watchman. It features the character known as Scout as an adult woman and I thought it a pretty decent effort. My editor, who was taken by the flashbacks to Scout's childhood, persuaded me to write a novel from the point of view of the young Scout. I was a first-time writer, so I did as I was told. I hadn't realized it had survived, so was surprised and delighted when my dear friend and lawyer Tonja Carter discovered it. After much thought and hesitation I shared it with a handful of people I trust and was pleased to hear that they considered it worthy of publication. I am humbled and amazed that this will now be published after all these years."[20]

Translations

Some translations of the novel have appeared. In the Finnish translation of the novel by Kristiina Drews, "nigger" in the original is translated as "negro" or "black" instead. Drews stated that she interpreted what was meant each time, and used vocabulary not offensive to black people.[21]

Controversy

Some publications have called the timing of the book "suspicious", citing Lee's declining health, statements she had made over several decades that she would not write or release another novel, and the death of her sister and caregiver two months before the announcement.[22][23] NPR reported on the news of her new book release, with circumstances "raising questions about whether she is being taken advantage of in her old age".[8] Some publications have even called for fans to boycott the work.[24] News sources, including NPR[8] and BBC News,[25] have reported that the conditions surrounding the release of the book are unclear and posit that Lee may not have had full control of the decision. Investigators for the state of Alabama interviewed Lee in response to a suspicion of elder abuse in relation to the publication of the book.[26] However, by April 2015 the investigation had found that the claims were unfounded.[27]

Historian and Lee's longtime friend Wayne Flynt told the Associated Press that the "narrative of senility, exploitation of this helpless little old lady is just hogwash. It's just complete bunk." Flynt said he found Lee capable of giving consent and believes no one will ever know for certain the terms of said consent.[28]

Marja Mills, author of The Mockingbird Next Door: Life with Harper Lee, a friend and former neighbor of Lee and her sister Alice, had a contrasting perception. In her piece for The Washington Post "The Harper Lee I knew"[9] she quotes Lee's sister Alice, whom she describes as Lee’s "gatekeeper, advisor, protector" for most of Lee's adult life, as saying "Poor Nelle Harper can't see and can't hear and will sign anything put before her by anyone in whom she has confidence." She makes note that Go Set a Watchman was announced just two and a half months after Alice's death and that all correspondence to and from Lee goes through her new attorney. She describes Lee as "in a wheelchair in an assisted living center, nearly deaf and blind, with a uniformed guard posted at the door" and her visitors "restricted to those on an approved list".[9]

New York Times columnist Joe Nocera continues this argument.[10] He also takes issue with how the book has been promoted by the “Murdoch Empire” as a "Newly discovered" novel, attesting that the other people in the Sotheby's meeting insist that Lee's attorney was present in 2011, when Lee's former agent (whom she subsequently fired) and the Sotheby's specialist found the manuscript. They say she knew full well that it was the same one submitted to Lippencott in the 1950s that was reworked into Mockingbird, and that Carter had been sitting on the discovery, waiting for the moment when she, and not Alice, would be in charge of Harper Lee's affairs.[10] He questions how commentators are treating the character of Atticus as though he were a real person and are deliberately trying to argue that the character evolved with age as opposed to evolved during development of the novel. He quotes Lee herself from one of her last interviews in 1964 where she said, "I think the thing that I most deplore about American writing—is a lack of craftsmanship. It comes right down to this—the lack of absolute love for language, the lack of sitting down and working a good idea into a gem of an idea."[10][29] He states that, "a publisher that cared about Harper Lee's legacy would have taken those words to heart, and declined to publish Go Set a Watchman—the good idea that Lee eventually transformed into a gem. That HarperCollins decided instead to manufacture a phony literary event isn't surprising. It's just sad."[10]

Others have questioned the context of the book's release, not in matters of consent, but that it has been publicized as a sequel as opposed to an unedited first draft.[9] There is no foreword to the book, and the dust jacket, although noting that the book was written in the mid-1950s, gives the impression that the book was written as a sequel or companion to Mockingbird, which was never Lee's intention.[9][15] Edward Burlingame, who was an executive editor at Lippincott when Mockingbird was released, has stated that there was never any intention, then or after, on the part of Lee or Hohoff, to publish Go Set a Watchman. It was simply regarded as a first draft.[15] "Lippincott’s sales department would have published Harper Lee’s laundry list", Burlingame said. "But Tay really guarded Nelle like a junkyard dog. She was not going to allow any commercial pressures or anything else to put stress on her to publish anything that wouldn’t make Nelle proud or do justice to her. Anxious as we all were to get another book from Harper Lee, it was a decision we all supported." He said that in all his years at Lippincott, "there was never any discussion of publishing Go Set a Watchman".[15]

Reception

Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times described Atticus' characterization as "shocking", as he "has been affiliating with raving anti-integration, anti-black crazies, and the reader shares [Scout's] horror and confusion".[16] Aside from this revelation, Kakutani notes that Go Set a Watchman is the first draft of Mockingbird and discusses how students of writing will find Watchman fascinating for that reason.[16] A reviewer for The Wall Street Journal described the key theme of the book as disillusionment.[30] Despite Atticus' bigotry in the novel, he wins a case similar to the one he loses in To Kill a Mockingbird.[31] Michelle Dean of The Guardian wrote that many reviewers, such as Michiko Kakutani, allowed their personal convictions and takes of the controversy that erupted before the publication to leak into the reviews. She defends the novel as a "pretty honest confession of what it was to grow up a whip-smart, outspoken, thinking white woman in the south... in a word, unpleasant", and stated that the book's bad reception is due to the "[shattering of] everyone's illusions...that Harper Lee was living in satisfied seclusion".[32]

Entertainment Weekly panned the book as "a first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird" and said, "Though Watchman has a few stunning passages, it reads, for the most part, like a sluggishly paced first draft, replete with incongruities, bad dialogue, and underdeveloped characters".[33] "Ponderous and lurching", wrote William Giraldi in The New Republic, "haltingly confected, the novel plods along in search of a plot, tranquilizes you with vast fallow patches, with deadening dead zones, with onslaughts of cliché and dialogue made of pamphleteering monologue or else eye-rolling chitchat".[34] On the other hand, Dara Lind of Vox states that "it's ironic that the reception of Go Set a Watchman has been dominated by shock and dismay over the discovery that Atticus Finch is a racist, because the book is literally about Scout — who now goes by her given name, Jean Louise — ...[who] has been living in New York, and quietly assumed that her family back home is just as anti-segregationist as she is".[35] In The New Yorker, Adam Gopnik commented that the novel could be seen as "a string of clichés", although he went on to remark that "some of them are clichés only because, in the half century since Lee's generation introduced them, they've become clichés; taken on their own terms, they remain quite touching and beautiful".[36] Maureen Corrigan in NPR Books called the novel "kind of a mess".[37] In The Spectator, Philip Hensher called Go Set a Watchman "an interesting document and a pretty bad novel", as well as a "piece of confused juvenilia".[38] "Go Set A Watchman is not a horrible book, but it's not a very good one, either", judged the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, citing among other flaws its "overly simplistic" plot.[39]

Alexandra Petri wrote in The Washington Post, "It is an inchoate jumble ... Go Set a Watchman is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a good, or even a finished book. For the first 100 pages it lacks anything that could even charitably be described as a plot. ... [T]he writing is laughably bad. ... I flung the book down and groaned audibly and I almost did not pick it back up even though I knew I had fewer than 100 pages to go. ... This should not have been published. It’s 280 pages in desperate need of an editor. ... If you were anywhere in the vicinity of me when I was reading the thing, you heard a horrible bellowing noise, followed by the sound of a book being angrily tossed down. ..."[40] Contrastingly, Sam Sacks of The Wall Street Journal praised the book for containing "the familiar pleasures of Ms. Lee’s writing—the easy, drawling rhythms, the flashes of insouciant humor [and] the love of anecdote".[41]

Author Ursula K. Le Guin wrote that "Harper Lee was a good writer. She wrote a lovable, greatly beloved book. But this earlier one, for all its faults and omissions, asks some of the hard questions To Kill a Mockingbird evades."[42]

The year it was released, the book won the Goodreads Choice Award in Fiction.[43]

.jpg)